Benfleet to Thameside Nature Park

Day Twenty-Nine

We left John on something of a cliffhanger last night. He had been ordered to ice his right shin within an inch of frostbite, neck down enough Ibuprofen to deflate the current PM’s ego, and learn everything he could about shin splits. This morning at seven thirty, he popped out his pop-up tent and after some yelping and hopping, declared he didn’t have shin splits. It had seemed mysterious: the one leg effected, the other in prime good health. A couple of hours on google had convinced him, but he had no alternative diagnosis.

That set me thinking. I remembered how the tiny cuts from brambles had allowed poisons from noxious herbiage to enter his system and inflate one of his ankles to look like that of a baby elephant. “Have you considered?” I asked him, over morning coffee sent over from Ali and Mike in the other van, “That you could be suffering from Long Hogweed?”

John removed the ice pack and frowned at his shin. “But it feels better this morning.”

“That’s because Long Hogweed is quite short.”

A frenzy of googling followed and he found the case of a Mancunian who had almost died from brushing against Giant Hogweed. The key word, I pointed out helpfully, was ‘almost’. John resolves to continue.

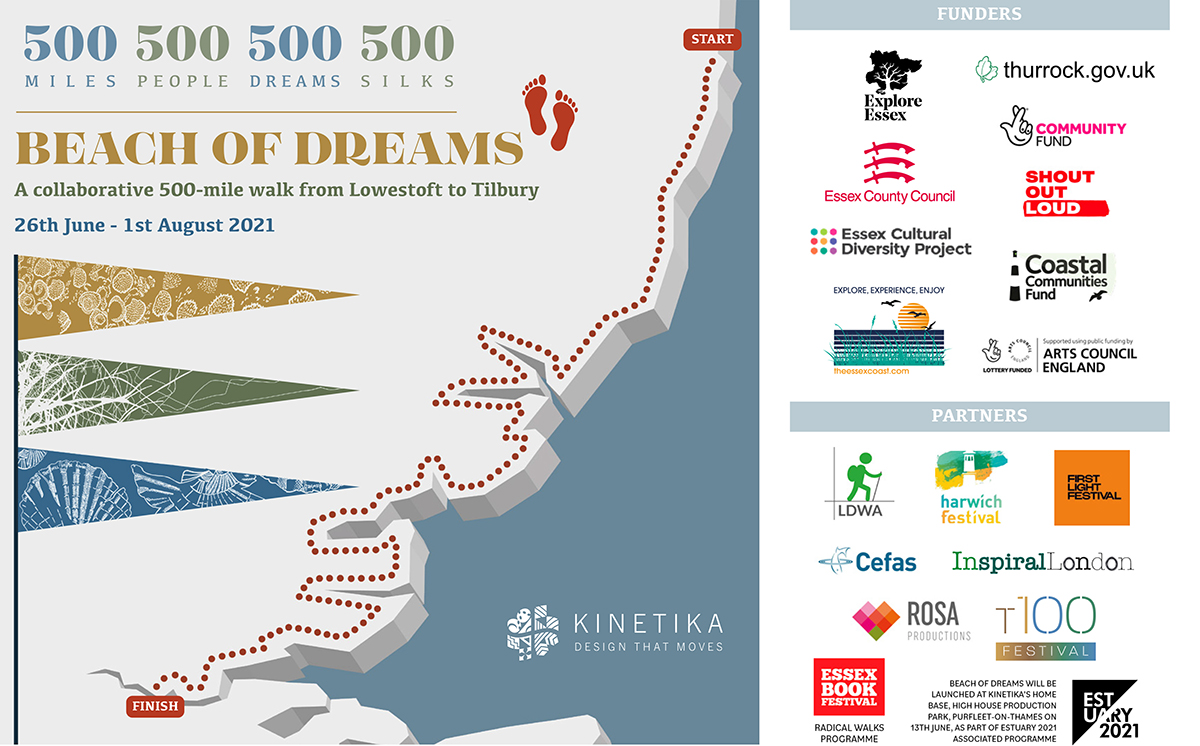

We start once again at Benfleet station and there’s quite a crowd of bouncy fresh people waiting for us. Keith has got a clipboard and looks like our leader for the day. He’s brought a gang from Inspiral London, a walking group who normally hike around the capital. This is out of their normal range and they eye John and I doubtfully as we slump onto the kerb, determined not to expend any extra energy. Ali is perkier, standing to explain the flags and our five-weeks of walking the coast. Keith details all the various loo stops, potential lunch points, and areas of interest, then we set off.

The map does not inspire much hope for this walk: there is a creek called Parting Gut, two sewage farms, a crematorium and the villages of Fobbing and Mucking. But in fact what we find is bird reserves and meadows of wild flowers dancing with butterflies and dragonflies. On the fringes of Pitsea Creek, I peel off to watch a herd of cattle mob grazing surrounded by birds. A local birder, Andrew, tells me that he has been coming here for 25 years and has spotted rarities like a marsh sandpiper from Central Asia and a phalarope from North America. “Spoonbills bred in the UK for the first time this year,” he tells me, “At a place called Abberton Reservoir.”

“We walked there!” I say, adding rather shame-facedly, “But didn’t see any spoonbills.” How could I have brushed so close to history and not noticed what was happening? Sadly, my dull wits are going to be exposed again, sooner than I would like.

Andrew thinks there are more birds now, since the RSPB started managing the wetlands, and there are species like egrets that have arrived and begun breeding. No doubt global warming is responsible, pushing the ranges of previously unimaginable rarities northwards.

The evidence of the human lifestyles that are behind that northward shift are all around us. Every hill we see, as Keith points out, is a landfill site full of London rubbish that has been covered and grassed over. He quotes someone that he describes as a ‘rubbish expert’, an oxymoron that I like. Keith retired from a city job and now leads walks in the capital, occasionally taking refugees on strolls to show them places that they can relax and enjoy. They are, of course, only the human spoonbills, heading north to find new grounds, but their lives are more dangerous and fraught. One boy, taken on a day trip to the seaside, went into shock. The day, intended as a pleasure, had triggered traumatic memories.

Our fellow walkers take a slower pace than we are used to; some suffer from heat exhaustion and need regular stops; they refuse to walk through cattle and require shade to sit down in. We seem weathered and hardier in comparison, even Hobblin’ John, but we should be, after almost a month.

There are home-made signs here, warning walkers not to stray off the footpath. But the path is overgrown and undetectable. In the pub at Fobbing, someone overhears an anti-immigrant diatribe. Two ladies walking behind me discuss their lives as scout leaders. It takes six hours of paperwork, says one, to get one hour outside with the group. On a recent trip the boys were sent alone into some woodland to find hidden teddy bears. Later there were panicky telephone calls from concerned parents who could not believe what their children had just done.

In Fobbing village the front gardens of many houses are covered in plastic astroturf. Most of it looks in need of a good hoover. At a gate to a field I spot a pistol lying in the grass. It is plastic and broken, but may have once been convincing enough to use in a bank job. Lunch is on a nice stretch of grass by a brook. Behind us looms the cranes of the new London Gateway port, where the longest container ships in the world can now dock. People eat avocado salads, sourdough breads and home-made humous. I can’t see any cheese and Branston sarnies, not even in my lunchbox which is a miserable hard-boiled egg and a lump of cheddar. I’d been banking on the bagel kiosk in Benfleet, but it is closed on Mondays. Anita puts me right about my claim, in a previous blog, that no one loves nuclear power stations. She collects them. Not that she keeps a few specimens in a glass cabinet in the living room, she visits them. Her favourite was Dungeness. Near the control room there was a vending machine that sold water, soft drinks and headache tablets.

One of the other walkers, J.D. Swann, stands up to talk about the nearby zoo that closed down. This field used to ring with the roars of lions and the trumpetings of elephants. J. D. looks like an interesting character. He is wearing a fusty outfit of tweed and carrying binoculars and a walking stick with a carved swan’s head. His trilby has a feather in it and his voice, when he addresses us all, is suddenly thespian and loud. Ali had told me he is an ornithologist, but he corrects this: “I’m an ornithological investigator.” He does not, however, seem very knowledgeable, not like Andrew. What is going on? All these contradictory and complex signals from the environment! Is he performing? Someone whispers that J. D. Swann is really an artist called Calum Kerr. I’m humbled, having been taken in. We are approaching the city like old-time rustical peasants, wide-eyed and innocent, waiting to be gulled.

We pass a field of sunflowers and a sign inviting us to take one. This small act of straightforward friendliness stands out. We are growing accustomed to hostility: warning signs, poisonous plants, and barbed wire. We simple souls must be on our mettles amid the nettles.

Our fourteen miles end, appropriately, on a dump: a long low hill covered in flowers and grassland that is humming with insect activity. Somewhere below us lies a thick and compacted stratum of total garbage.

Kevin Rushby

Beach of Dreams Blog

Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5 Day 6 Day 7 Day 9 Day 10 Day 11 Day 12 Day 13 Day 15 Day 16 Day 17 Day 18 Day 19 Day 20 Day 21 Day 23 Day 24 Day 26 Day 27 Day 28 Day 29 Day 30 Day 31 Day 32 Day 33 Day 34 Day 35

Route: Walk 29

Gallery of the Miles

See all the mapped miles on the Storymap, find a selection below.

![]()