Canvey Island

Day Twenty-Eight

We start the day on a high, a breakfast bagel with coffee outside the Golden Bagel next to Benfleet railway station. The joy of porridge, our habitual van-cooked breakfast, has faded over the weeks and now I have begun to loathe the colourless gloop. John seems to still like it, but then he is living in the kind of pop-up tent that was built to survive one night at a festival. Porridge is a luxury. Meanwhile, Ali seems to survive only on hot water and lemon juice. It must work since she is the only one who never complains about the wear-and-tear we are suffering.

Today we are circumnavigating Canvey island and we have Phil to guide us. Phil knows every imaginable secret that Canvey keeps. “In Edwardian times a character called Hester arrived and decided to make it a new world, a Utopia. He promised a monorail run on electricity, winter gardens and beautiful Scandinavian-style houses.” None of this materialised, but people came and some stayed. They built cabins and eeked out a living. Canvey, or The Island, as its inhabitants knew it, began to develop something of a mystique.

We get on the sea wall and meet Barbara who has lived here for 70 years. “My Dad would repair or build boats in the garden and then we’d go off on holiday to the River Medway.” It sounds like Swallows and Amazons, but in 1953 the dream took a bad knock. Floods ripped across the island. Barbara’s parents were woken in the night by a knock on the window and told to get out. Not everyone was lucky, 59 people died, many from hypothermia. As a result the sea wall was raised and now it seems that most of the island is below sea level. When the Canvey Island football team play, container ships pass by above them which must disconcert the opposition a bit.

Below the sea wall is a ledge which can be walked around and most of it is painted sky blue which makes it seem unaccountably tropical. Wild swimming became popular in lockdown. Occasionally this scene is given an added twist by the appearance of Hasidic Jewish people who have moved here in the last few years.

Phil’s real love is music, and particularly the period known as the Thames Delta Blues. How it all started no one really knows, but somehow living in simple wooden cabins in a muddy delta struck a chord and American R&B became popular. This was the early 1960s and over the river in Dartford two teenage wannabees called Keith Richards and Michael Jagger were swapping records. On Canvey, a teenage boy called John Collinson went to a gig in nearby Pitsea and saw a Chicago bluesman called Howlin Wolf. Quite how this titan of the blues came to be playing in an obscure Essex village is unknown, but it had a huge effect on Collinson. Reborn as Lee Brilleaux, singer and harmonica player, he formed a band called Dr Feelgood with another Canvey lad, John Wilkinson, who soon changed to being Wilko Johnson.

Phil is quite clear that Lee Brilleaux was his hero. As we move under the ominous gantries and jetties of the oil and gas end of Canvey, he explains. “He was just so authentic. I’d never seen anything like it. Live at the Canvey Club, they were incredible.”

Fortunately I know what he’s talking about having seen Dr Feelgood in Nottingham some time in 1977. They were like a force of nature: a raw and brutal rhythmic assault that took my breath away. Not long after that Wilko left the band, taking his song-writing skills with him. Dr Feelgood began to survive on reputation. There were no more hits and Brilleaux died in 1994 at his home in Leigh on Sea. It was only then that Phil realised his life-long hero had been living around the corner from him for the last ten years. “I’d never have dared speak to him anyway.”

He points out the jetty where the album cover photo for their first LP, Down at the Jetty, was taken, just near the clapboard Lobster Shack pub. “In the old days the pub had a reputation for violence: there’d be bare-knuckle fights and also scraps with the customs men – smuggling was rife.”

One of our local walkers, Jason, is the living proof of the devotion Canvey inspires. “I live in the house I was born in. I did move away for a couple of years, but soon came back.”

It’s hard to fathom as an outsider: the saltmarshes look like other Essex saltmarshes; the sea wall is a sea wall; the scrubby vegetation undistinguished, it is only an island at low tide by virtue of a six-inch wide trickle of brown water. On the far side, however, with the full breadth of the Thames estuary in sight, and vast container ships small on the horizon as they steam upriver, there is a feeling of space and emptiness that is hard to find near a capital city. The tide rushes in and the surge of water slaps at the sea wall. “It’s an island,” says Barbara, “And when I was young, no one came here. It was too remote.”

I think of her childhood holidays, setting sail for distant shores, and feel the magic. We blast around the empty northern end of the island, swatting at horse flies. John is way behind suffering from shin splits. It would be a hard knock if he were not to make it now, after 417 miles.

Kevin Rushby

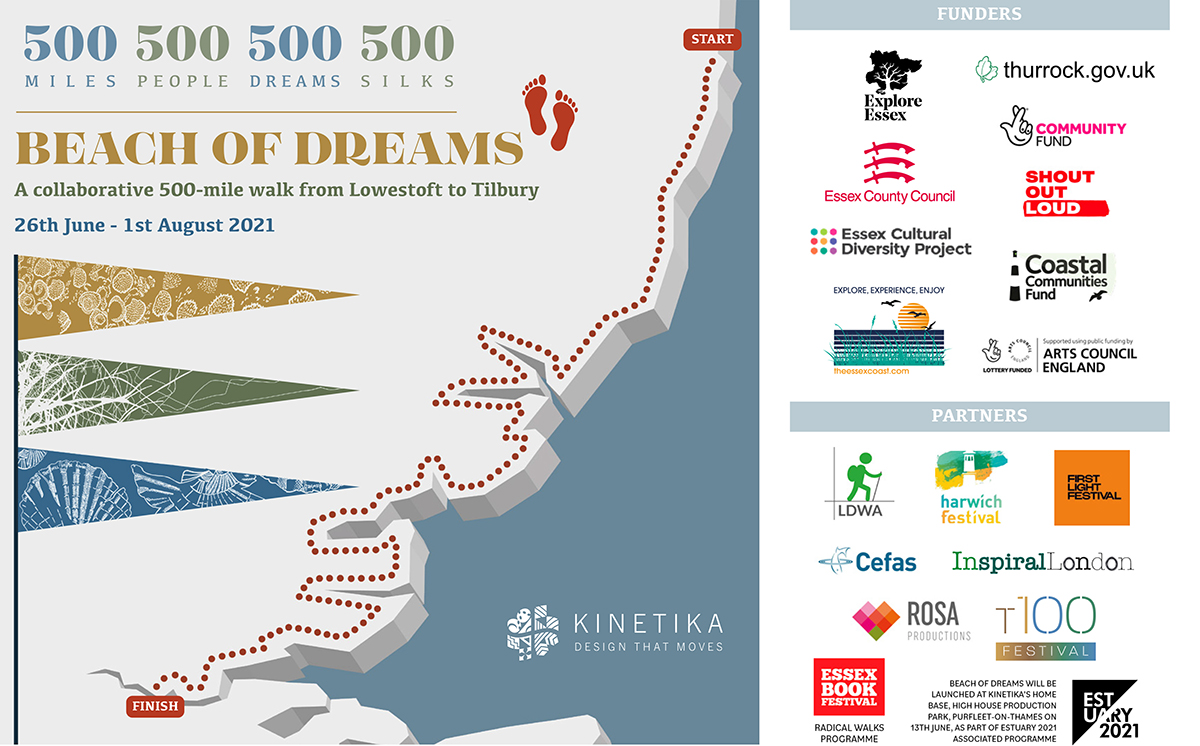

Beach of Dreams Blog

Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5 Day 6 Day 7 Day 9 Day 10 Day 11 Day 12 Day 13 Day 15 Day 16 Day 17 Day 18 Day 19 Day 20 Day 21 Day 23 Day 24 Day 26 Day 27 Day 28 Day 29 Day 30 Day 31 Day 32 Day 33 Day 34 Day 35

Route: Walk 28

Gallery of the Miles

See all the mapped miles on the Storymap, find a selection below.

![]()