Ipswich to Shotley

Day Nine

Some days the wheels fall off. Your feet ache and it spreads to your calves which set off the hips and the old back ache kicks in. For a while the others in the group could occasionally be glimpsed, forging ahead, then I was alone. Then I missed the footpath sign, the one buried in nettles, and went round in circles. Yesterday was like that. For some painful minutes it looked like I would become the Captain Oates of Orwell Country Park on the outskirts of Ipswich which, on the scale of heroic failure, didn’t seem very high. John was lagging behind too, struggling with an ankle problem when I caught up with him. At least we had each others company, though it was mainly silent.

On the banks of the River Orwell we got directions from a couple who spoke a little broken English and made it to the finish. Today we got up and John decided that he had to visit a chemists and get medical advice. Fortunately there was a place en route through Ipswich’s suburbs and he set off early, hobbling like a man who had spent too many hours riding an exceptionally wide Shire horse, promising to wait outside for our arrival. It would prove to be the last we would ever see of him.

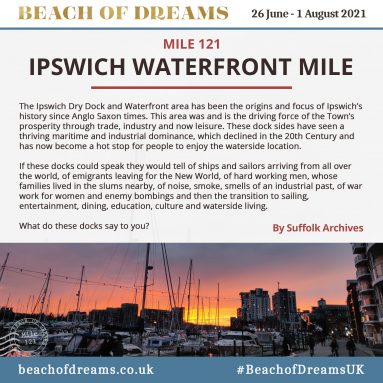

The quayside in Ipswich is an impressive location. The old derelict warehouses have been converted into smart apartments; university buildings stand where sacks of grain used to be swung onto sailing barges. While Ali is organising flags and meeting the day’s walkers, a passer-by asks me what we are doing. He is soon pointing out where swift nest boxes are located on some new buildings and the peregrine falcon nest on top of another. “But they’re not there now.” Nor are the swifts in evidence.

We wind through the Ipswich waterfront and reach the chemists. No John. We call. He’s been sent to Casualty. Long distance walking is not for everyone. He was a good guy, like Captain Oates in some ways. I’ll miss him.

Eventually we reach fields and talk to Oliver Paul whose family farm the land on this side of the River Orwell, the Shotley peninsula. Many of their acres are intensively farmed for potatoes, onions and carrots, but some has been turned over to regenerative agriculture, with mixed results. “Dormice seem to be suffering a decline,” he tells me, “But nightingales are doing well.” We walk on through his woods, but do not hear nightingales.

We wander down through woods and bracken to the riverbank. Several big trees here are dead: some are ash, but there are oaks too, killed by repeated salty floods, a harbinger of rising sea levels. Despite this the landscape is utterly gorgeous in the sunshine. At Pin Mill we reach a paradise of old wooden boats and sturdy country architecture. Anthony Cullen who has a photographic studio here shows me a set of prints from pictures taken by Arthur Ransome, author of Swallows and Amazons. Although usually associated with the Lake District, Ransome moved here in 1938 and ordered a traditional sailing boat, Selina King, to be built. The photos catalogue that process in fascinating detail. In several pictures, Ransome’s wife, Evgenia, stares resolutely away from the camera. Perhaps she didn’t approve of the boat, she was certainly critical of Ransome’s writing – just the kind of spur any writer needs – but perhaps she had learned to be cautious about public exposure; after all, she had been private secretary to Leon Trotsky at the time of the Russian Revolution. Anthony plans to put these historic, and beautiful, photographs on permanent display in his studio which was once Ransome’s sail loft.

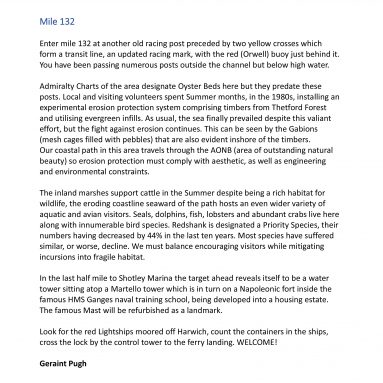

On the final stage of the walk we are joined by Ian Peters, a keen local ornithologist who has been ringing birds in these marsh meadows for over 50 years. Sadly it has been mostly about decline. “We never see spotted flycatchers now,” he says as we push through head-high hogweed on the bankside path. “Last year the Ringed Plovers produced one chick. I can’t imagine it survived.” Ringed plover chicks are no bigger than a large bumble bee when they hatch and easily snaffled up by a dog. “It’s so sad,” he says, “Even on those extendable leads, they can do damage. I haven’t seen any Ringed Plovers this year.”

We stand together on the path and scan the foreshore with binoculars. One crow steps through the mud. Across the estuary, the hum of Felixstowe container port is audible. This is Britain’s busiest port and the place where the super ship Evergiven was bound before she got stuck in the Suez Canal. Ian points out that the buildings associated with the port have been given the names, Avocet and Dunlin House, presumably to commemorate the birds we don’t see today.

At the end of the day, I am typing this blog in my campervan when a familiar figure appears. He is shuffling along, head down with grim determination. It’s John, the rare bird that we had presumed extinct, back from A&E. He has had his ankle problem treated and is fine. He has walked the 12 miles behind us, determined to carry on. In fact, with all that shuffling around Ipswich General, he has covered 17 miles today and is technically ahead. Annoyingly, this means that I am, once again, the weakest link.

Kevin Rushby

Beach of Dreams Blog

Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5 Day 6 Day 7 Day 9 Day 10 Day 11 Day 12 Day 13 Day 15 Day 16 Day 17 Day 18 Day 19 Day 20 Day 21 Day 23 Day 24 Day 26 Day 27 Day 28 Day 29 Day 30 Day 31 Day 32 Day 33 Day 34 Day 35

Route: Walk 9

Gallery of the Miles

See all the mapped miles on the Beach of Dreams Storymap, find a selection below. Slideshow images are by Mike Johnston.

MILE 124

![]()