Purfleet Beacon to Grays

Day Thirty-Four

I almost died of shock. There it was. The pop-up tent abandoned and empty. No sign of Hobblin’ John Hogweed at all. His boots, the subject of a court order condemning them to extermination, were gone. His rucksack was gone. I can’t say I hadn’t foreseen this moment. There were signs of physical and mental deterioration as we passed the 400 mile mark. He had begun saying contradictory and irrational things like, “I can’t wait to get back to Sheffield” and “Maybe I’ll just keep going, get round Kent and head for Cornwall”. I’d caught him feeding his breakfast, the delicious thick porridge I made for him, to the chickens on the campsite. But I had always assumed he would knuckle down and make the 500. I know he needs the prize money (don’t tell him: there isn’t any) and would pull himself through.

Then I saw him, already sitting in the van, ready to go this morning, fifteen minutes early. He looked exhilarated and happy. Ali too. And me. I think my blog from yesterday has scoured out all the bitterness about Thurrock. Now the sun is out, I feel optimistic and ready to be persuaded that hope still exists. This is our penultimate day. Short of an Act of God, we will make it.

The start is by the beacon on the riverbank at Purfleet from where we set off downriver. I talk to Saira, an inspiring young woman of Pakistani heritage, who got into walking at an early age and has since been encouraging women of similar backgrounds to try it out. “My Dad took us up to the South Downs when we were young and since then I’ve never stopped.” Her love of exploring and discovery has unearthed many hidden gems in the capital which she shares through group walks (www.livinglondon.org).

Behind us are Bola and Remi, chatting in Yoruba. Remi has been dragged out the house by her friend Bola, who loves walking. Remi has never gone for a walk in Purfleet, despite living here for eight years. They are both keen cooks and I show them the wild rocket that is growing on the edges near the sea wall. Can they get everything they need for Nigerian cuisine in Thurrock?

“Oh yes,” Bola tells me, “Yams, okra, water greens, ewuro bitterleaf, efo spinach – it’s all here in Grays.”

I’m impressed.

Out on the sea wall, I am waylaid by the jetties, climbing some ladders and then down underneath into a dark world of mud and pipes. I slip and stumble. Is this the Act of God where I fall into the slime and become a piece of flotsam and jetsam for future archaeologists to unearth?

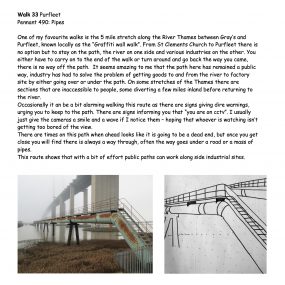

I survive and clamber out, back into the sunshine next to the wall of graffiti. This concrete is an elongated communal masterpiece, worked on by hundreds, a visual feast that knocks anything upriver at Tate Modern into a distant second place. I come across three men spraying while listening to music. “You’re surprisingly old,” I tell them, not very diplomatically, but they take it with a laugh.

“We all started when we was about 13,” Crane (his tag name) tells me, “But now we got back into it.”

The pandemic was instrumental for this, allowing time. They come down at dawn and work all day, weather permitting.

“I never know what will come out,” Crane says, “It just happens. But it will be my tag when it’s done.”

The art will be done by nightfall, but it may not last long. Some paintings might last only a day or two before someone sprays over it. If the tag and the work is respected, others can stay for a few months, but everything is transient. This is a world away from the art market with its inflated egos and prices, and so much better for it.

I’m now way behind the group and step away from the river to visit St Clements Church, an iconic film location from Four Weddings and a Funeral. In the climatic scene, Gareth, played by Simon Callow, is buried in this flint-walled 11th century church, right next to the steaming soap factory.

Staring up at the church I find, Fotis, looking a bit starry-eyed. “I’m having a cultural moment,” he says, “When I was a boy in Greece, that film scene meant a lot to me. It was great film-making, but also I thought Britain must be incredible: imagine the kind of place where you get such crazy juxtapositions as this. I found that very inspiring.”

I catch up with the group as they walk into Grays’ town centre. A rapper is holding court on the pedestrianised street while the African, Asian and European shops are doing good business. A bakery hands out samples of its cakes and while I greedily sneak two pieces, I talk to Jay who came to Thurrock 30 years ago. “I was born in Tanzania,” she says, “But there was anti-Asian problems in the early 70s.” The family moved to Gujarat and then London. “At 22 I was quite innocent. When my Dad showed me a photo of a man, I said he looked alright. Next thing I was married, but he proved to be very hot-tempered, bashing me up.”

Eventually Jay escaped, and taking her young son with her, headed to a place where she knew nobody: Thurrock. “It was so welcoming,” she says, “I was one of the first Asians here, but I have never experienced any racism, nor my son.”

At the end of the walk, I catch up with Bola and Remi again. “Walking is actually enjoyable,” says Remi, a bit surprised by her discovery. “The graffiti wall was amazing – I’m definitely gonna bring my boys down to see it.”

I leave everyone there and set off back into town. I want to explore those world food shops. There’s a good Nigerian restaurant too, called The Tasty African.

Kevin Rushby

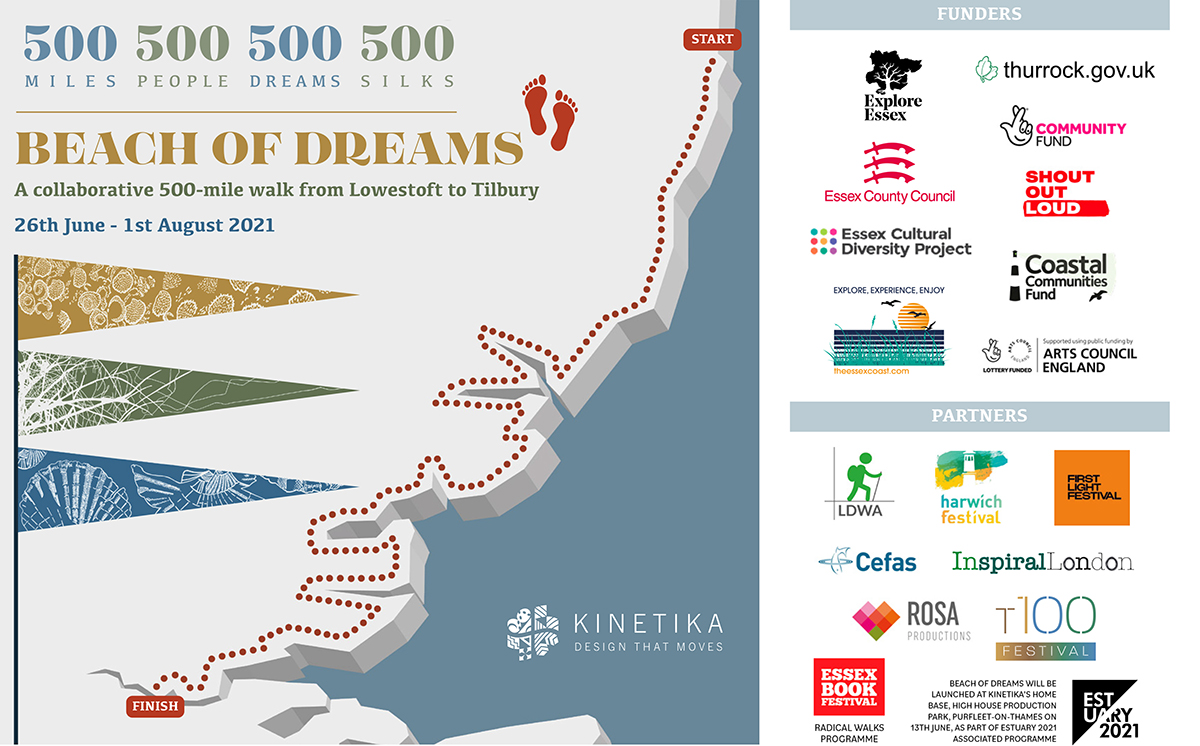

Beach of Dreams Blog

Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5 Day 6 Day 7 Day 9 Day 10 Day 11 Day 12 Day 13 Day 15 Day 16 Day 17 Day 18 Day 19 Day 20 Day 21 Day 23 Day 24 Day 26 Day 27 Day 28 Day 29 Day 30 Day 31 Day 32 Day 33 Day 34 Day 35

Route: Walk 34

Gallery of the Miles

See all the mapped miles on the Storymap, find a selection below.

![]()