Langdon Hills to Ockendon

Day Thirty-One

I suppose there was an assumption, at the start of the walk, that by the end things would get easier. We would be leaner and fitter and summer would be in full swing. How little did we know. In those heady days, Hobblin John Hogweed was a strapping young man full of vigour, not the hollowed out shadow I see this morning, stumbling out of his pop-up shanty tent and pulling on a pair of cold damp socks while scratching his mozzie bites. He looks ten years older than when I first met him a month ago.

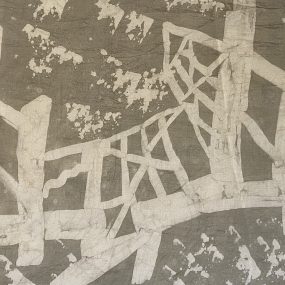

We start at Langdon Hills and today there is a large party of local people ready to stroll with us down through the woodland to an area known as the Plotlands. There is a nice chap from Essex Wildlife Trust, who manage the area, ready to stop the walk and give short talks on points of interest. We wander down through the trees and see the first signs of what was once a community of people living here: concrete paving slabs, disappearing into the undergrowth, and bits of concrete and rubble. Some of the forest looks like secondary growth, the tree thinner and the shrubs thicker. That’s where the Plotlanders lived.

In the 1870s an agricultural depression hit Britain as cheap grain from the USA began to undercut local production. South Essex was vulnerable as the farms were on marginal heavy clay, prone to turning into mud. Farmers sold out to entrepreneurs who then sold lots of around 140 by 20 feet to Londoners keen to build holiday homes. The schemes were popular with demobbed soldiers from WWI, and some simply moved in. There was no sewage, no electricity, and sometimes no water, but that didn’t deter resourceful East Enders who threw up sheds, huts and bungalows with abandon.

We come to a clearing on a hillside where several apple trees and wild plums are thriving. “This was Tom’s plot,” says our guide.

I hear an Essex voice next to me mutter. “No, this was Louie’s place.”

A lady in her 70s, Chris, is listening carefully, but disagreeing with some of what is being passed off as history. When we move on, I ask her how she knows. “I grew up here,” she tells me. “My Mum and Dad were East Enders and they’d bought a plot down the hill in the early 1930s as a holiday home. Dad built a wooden cabin. When we got bombed out in the Blitz, we came to live here.”

Chris had grown up in these woods. “It was a good childhood,” she tells me. “We didn’t have electricity, but we grew our own vegetables and fruit and I had lots of freedom.”

Her daughter standing next to her remembers visiting her grandfather who had stayed here well into the 1970s. “He was a pioneer homesteader,” she says proudly. “Like out in America. They were working class and they worked hard – and they were creative.”

The guide is telling the group how hard life was for the plotlanders. “This path would be all mud in winter. The houses were shacks and there was no sewage system.” He paints a picture of squalor.

Chris is not impressed. “We were happy here.”

We move down to a plotland house that is still standing. “This was the doctor’s house,” explains the guide, “He lived here with his wife and three sons.”

Chris and daughter exchange a look. “No it wasn’t. He wasn’t a doctor and he only had two boys. They lived in that shed at the side until they built the house.”

This is how history gets written, I’m thinking. Perhaps the written records do show a doctor living here, with three sons, but the reality may have been different. Who gets to decide? Probably the people with display boards and visitor centres, rather than those who were there. Chris goes off the track and finds some trees that she planted as a child. Her daughter seems angry. “If you listen to the mainstream media, you’d think all white people were slave owners, but people like us had nothing to do with that. My grandad came out here to live an independent life. He was a home-steader.”

I have my phone in my hand and push it in my pocket. She notices. “Are you recording this?”

I’m not, but I’d forgotten that I am a member of the mainstream media and in some eyes, totally unreliable and suspect. I slip around the back of the plotland bungalow which has been carefully restored to show life inside. An enamel kettle on the neat stove, a Belfast sink, a scrubbed floor and stone jar containers on the ledge. Is this really what it was like? It seems more like something from an advert for Aga stoves.

In the car park outside the swish visitor centre, another chap is explaining how rubble and concrete can make good materials to plant flowers. There are several flower beds dotted around among the Range Rovers and BMWs. The cafe is busy serving lattes and cappuccinos. Chris’s daughter is in full flood, but I’ve lost track of what she is saying. Immigration and religion come into it.

After a break we walk back up into the woods. Phil reminds me that when Winston Churchill went to talk to the plucky East Enders during the Blitz, he was jeered off. King George VI was too, I remember reading. The people who came out to the plotlands were already fiercely independent and suspicious of authority. They are traits that can be traced through to today, perhaps even fuelled the Brexit leave vote. I have that feeling you get when you rip up the floorboards and see the job is bigger than you ever imagined. The rifts in British society are vast and can appear at the unlikeliest moments. If we embarked on this journey, hoping for discussion and exchange of views on the coast and its future, then we are certainly achieving our goal.

Leaving the large group behind, the Beach of Dreams walkers press on, heading down on to the estuary plains, skirting fields of wheat and barley then passing through entire ranges of hills, all of them landfill sites. The sheer magnitude of what lies beneath is awesome, the endless crap that the capital spews out daily, all finishing here to be tucked away under grass and forgotten about, hopefully.

Then the dark clouds that have been threatening move in and the deluge begins. By South Ockenden we are soaked and cold. In the street, a screeching gang of children stand by the road so that passing Range Rovers and BMWs can shower them in filthy water.

Kevin Rushby

Beach of Dreams Blog

Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5 Day 6 Day 7 Day 9 Day 10 Day 11 Day 12 Day 13 Day 15 Day 16 Day 17 Day 18 Day 19 Day 20 Day 21 Day 23 Day 24 Day 26 Day 27 Day 28 Day 29 Day 30 Day 31 Day 32 Day 33 Day 34 Day 35

Route: Walk 31

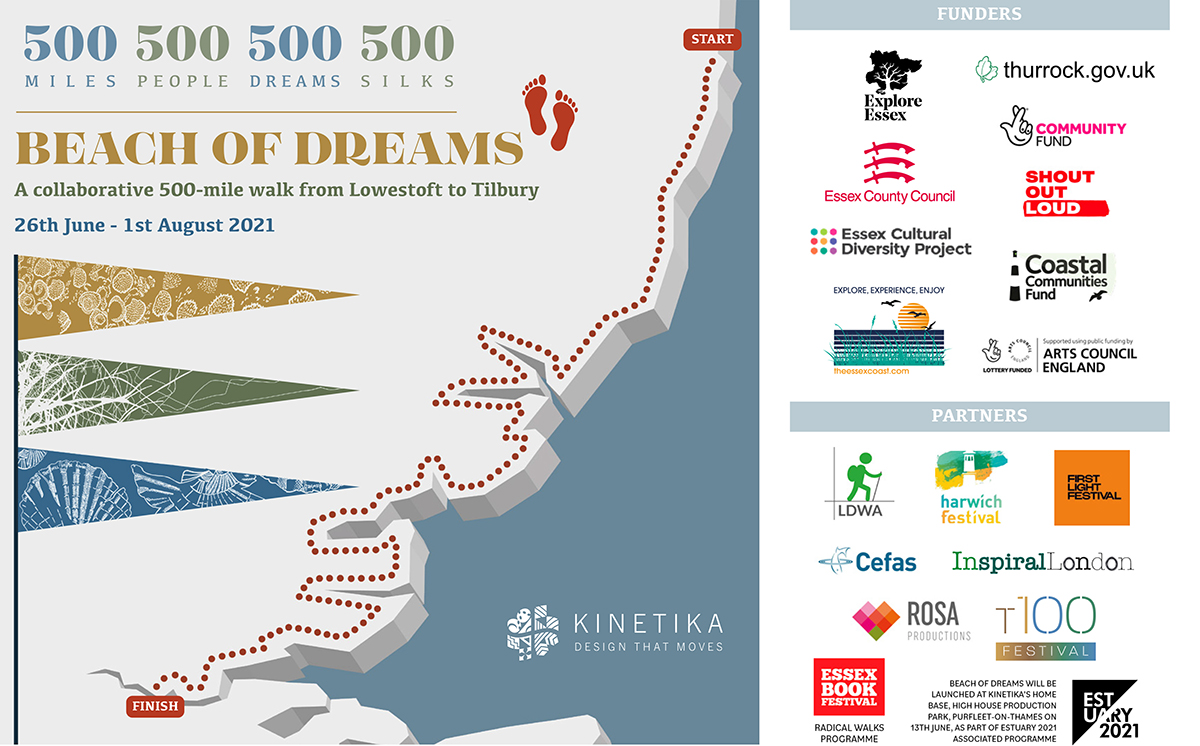

Gallery of the Miles

See all the mapped miles on the Storymap, find a selection below. Slideshow images by Mike Johnston.

![]()