Hullbridge to Paglesham

Day Twenty-Four

Just when you think it’s going to be okay, when the aches and pains have faded and the blisters are a distant memory. When each day passes and you feel stronger and you’re getting in the rhythm. That’s the moment to rip your foot open on a rusty nail. There was a second while I thought, this cannot be happening, then the blood started dripping off my heel. I strapped it up, put some weight on it, and got myself to the starting point at the slipway for the yacht club at South Woodham Ferrers, all the doubts of the first week once again alive. Would I make it? Is this where it all ends?

Doug was there with a rowing boat called Forget Me Knot and rowed myself and Colin across the river. There was once a bridge here that fell down, and then a ford that got washed away. Doug points out Brandy Hole, a spot that smugglers would run for when the excise men were on their tails. Then, according to legend, they would throw their barrels overboard weighted down with salt that would slowly dissolve. When the customs men had gone home the barrels would resurface. This sounds to me like the most ridiculous story imaginable, so perhaps it’s true. What does seem significant is that everyone has a smuggling story and the sense of a place that lives by its own rules is still strong. On the far side of the creek two taciturn sun-burned men are washing their horses in the water after riding down in gigs. The horses buck and thrash while a flotilla of swans look on.

Our path takes a long loop away from the water, passing through fields and isolated houses. Most are plastered with ‘Private’ signs. There’s one yard that is protected by rolls of razor wire and security fencing that does not let you see inside. The sturdy gates have a sign ‘Beware of the dog. It will bite you.’ On each pillar is a CCTV camera. It’s not a germ warfare research lab, or a gold bullion depository, not even a diamond mine. It’s a car repair workshop. Further on, a lovely house with immaculate country garden bisected neatly with an ugly metal fence and Keep Out signs. There is also a neat grey marble column that is inscribed with the words ‘In Memory of Fambridge Airfield. 02. 1909- 11. 11. 1909. Dedicated to all units and personnel based here’. In fact, Fambridge was Britain’s first ever airfield, but it was early days for aviators and no one actually got off the ground before it closed down, having lasted nine months.

Down in South Fambridge there’s a Triumph Dolomite sitting by the road. I glance inside and see a skeleton and an alien in the front seats, a skeleton of an animal in the back. Sometimes it’s hard to keep up with the unexpected in Essex.

We take a leafy path out towards the sea wall when something starts biting me around the knee. Ants? As I am well behind the others and there is no one around, I drop my trousers and hunt the beast. It takes a minute to locate the ant. When I stand up, a family of six are watching me. “Awright Mate?”

“Yes, fine. Sorry. Ants in my pants.” I pull up swiftly and tighten my belt.

“No worries.” They are obviously local and well-used to the unexpected. “To be fair,” says the Dad thoughtfully, “There’s plenty of ’em about down ‘ere.”

John and I leave Ali and local walker, Tessa, to swim, and press on. My foot had given up complaining, but now restarts. At some point in every day, there comes a moment when you have to focus and bang out a rhythm. We don’t speak. The landscape remains the same: a grassy bund that curls away endlessly. You do two miles and are almost back to where you were an hour before, only a ribbon of muddy creek separating the two points. In one place, a particularly unattractive tract of mud and concrete debris is marked with a new sign: ‘Private’.

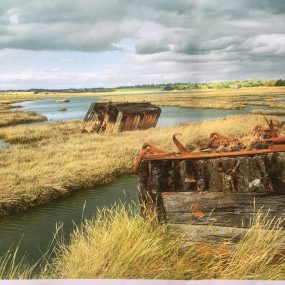

I forge ahead and come to the sea wall along Paglesham Creek. After a WWII gun emplacement, I pass the ruins of a steamer sinking into the mud. Beyond it is a rickety fence of green wire, enclosing a featureless stretch of mud. There are no signs, but I reckon this is perhaps the most significant stretch of featureless mud in the world, a place of incredible significance in the history of ideas and human progress. It is the last known resting place of HMS Beagle, the ship that carried Charles Darwin on his heaven-shaking expedition around the earth. Ground radar studies have shown the hull, approximately 21′ down in the mud. The Beagle had been brought here in 1845 to be a mid-river coast guard station, a base for anti-smuggler operations, then later dragged to the muddy bank and the superstructure dismantled. There is nothing that I can see to mention it’s presence.

All along this journey, we have seen valiant efforts to revive and repair historical artefacts. Money has been spent on concrete bunkers where atomic warfare experiments were once conducted; expertise has been lavished on traction engines and motorbikes; time and effort are going into boats that were pirate radio stations, there’s even that memorial to an airfield where no one ever flew a plane. But to see what was the most important ship that ever sailed, the vessel that incubated the discovery of evolution, just abandoned and unmarked is sobering. There should be a museum, a replica vessel with a precise reproduction of Darwin’s cabin, a visitor centre, a cafe and bookshop. Where are they? There is only a few oystercatchers and some lovely clumps of golden samphire. I hobble off to the pub.

Kevin Rushby

Beach of Dreams Blog

Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5 Day 6 Day 7 Day 9 Day 10 Day 11 Day 12 Day 13 Day 15 Day 16 Day 17 Day 18 Day 19 Day 20 Day 21 Day 23 Day 24 Day 26 Day 27 Day 28 Day 29 Day 30 Day 31 Day 32 Day 33 Day 34 Day 35

Route: Walk 24

Gallery of the Miles

See all the mapped miles on the Storymap, find a selection below. Slideshow images are by Mike Johnston.

![]()